Bridging Worlds: Understanding the Paradigms That Shape Ecological Thinking

How mindsets clash, converge, and evolve in regenerative conversations today.

We live in a world where carbon credits are traded like commodities, yet no one asks if the forest is still alive.

Most of our so-called sustainability strategies come not from wisdom, but from fear — of regulation, of reputational risk, of scarcity. This fear, born from separation, has led us down a path of reduction, measurement, and mitigation. But mitigation is not salvation. It is simply a slower death.

If we are to truly shift — if we are to reconcile with life — then we must understand that behind every ecological action is a paradigm of consciousness. Behind every forest policy, a mindset. Behind every restoration project, a worldview. And not all are created equal.

The path from extraction to regeneration is not linear. It is a stairway of paradigms.

For the past twenty years, I’ve been studying the language of paradigms — not just as intellectual frameworks, but as living codes that shape how we perceive, decide, and relate. And yet, every time I speak of Nature, Biodiversity, Aliveness, or Regeneration, I can feel the shift in the room.

It’s as if I’ve suddenly begun speaking a foreign dialect — one that doesn’t quite translate in the culture of quarterly reports, KPIs, and carbon markets.

Sometimes I’m gently nodded toward the sustainability team. Sometimes toward CSR. Often, the conversation quietly closes before it ever begins. Not because people don’t care — but because the language feels unfamiliar, perhaps even risky.

That discomfort is not personal — it’s paradigmatic.

I first explored this idea of “blue pill blindness” in my essay The Courage to see, tracing how the extractive mindset blinds us to nature’s real value — and how the courage to see becomes the first step toward regeneration.

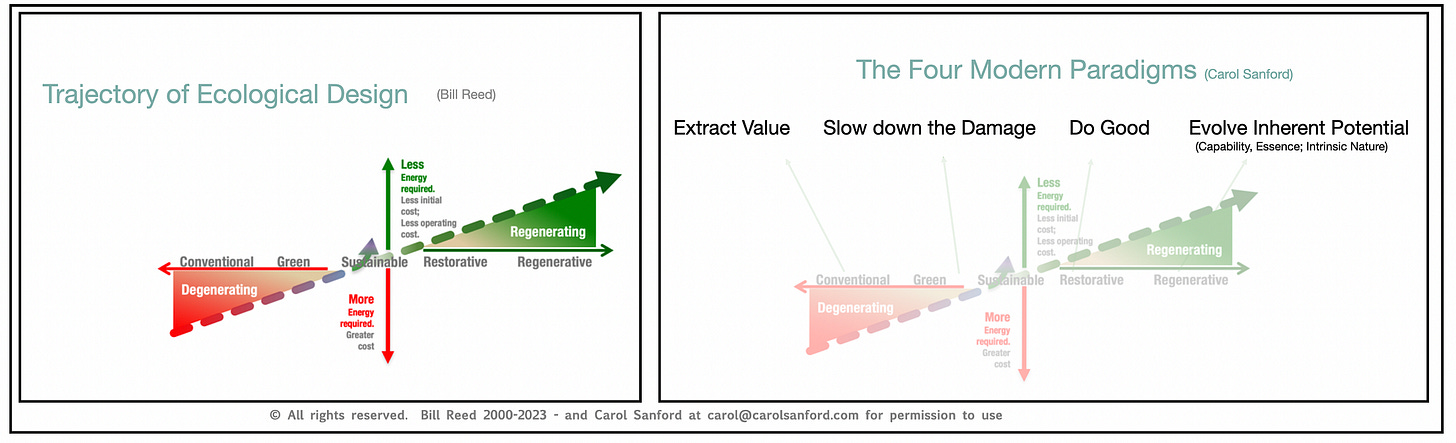

So I’ve spent years searching for bridges. Bridges between worlds. Between extractive logic and living systems. Between profit metrics and potential. And the most generative bridges I’ve found are the five paradigms of ecological design, as articulated by Bill Reed and Carol Sanford.

What follows is not a theory, but a working exercise — an attempt to name the archetypes that live within each paradigm, so that we can meet them with compassion, design more wisely, and invite deeper transformation — not by overpowering, but by speaking the language of where someone already is.

This is a working exercise — an attempt to sense and map the underlying archetypes of consciousness that show up when we speak of regeneration.

Whether we’re designing regenerative systems, building fundraising narratives, or hosting conversations about aliveness, co-evolution, and systemic transformation, we often encounter not just differences in knowledge or comfort zones — but entirely different levels of sense-making. These are not merely obstacles of ignorance, resistance, or language.

They are expressions of paradigm.

You can feel them emerge when a discussion about life, place, or potential is immediately redirected to profit, ROI, or corporate social responsibility. Suddenly, you’re speaking two different dialects of consciousness — one nested in living systems, the other in extractive logic.

This diagnostic is an evolving effort to define the archetypes of ecological consciousness.

It is not a judgment. It is a map. And like all maps, it simplifies — but hopefully in service of clarity, dialogue, and movement.

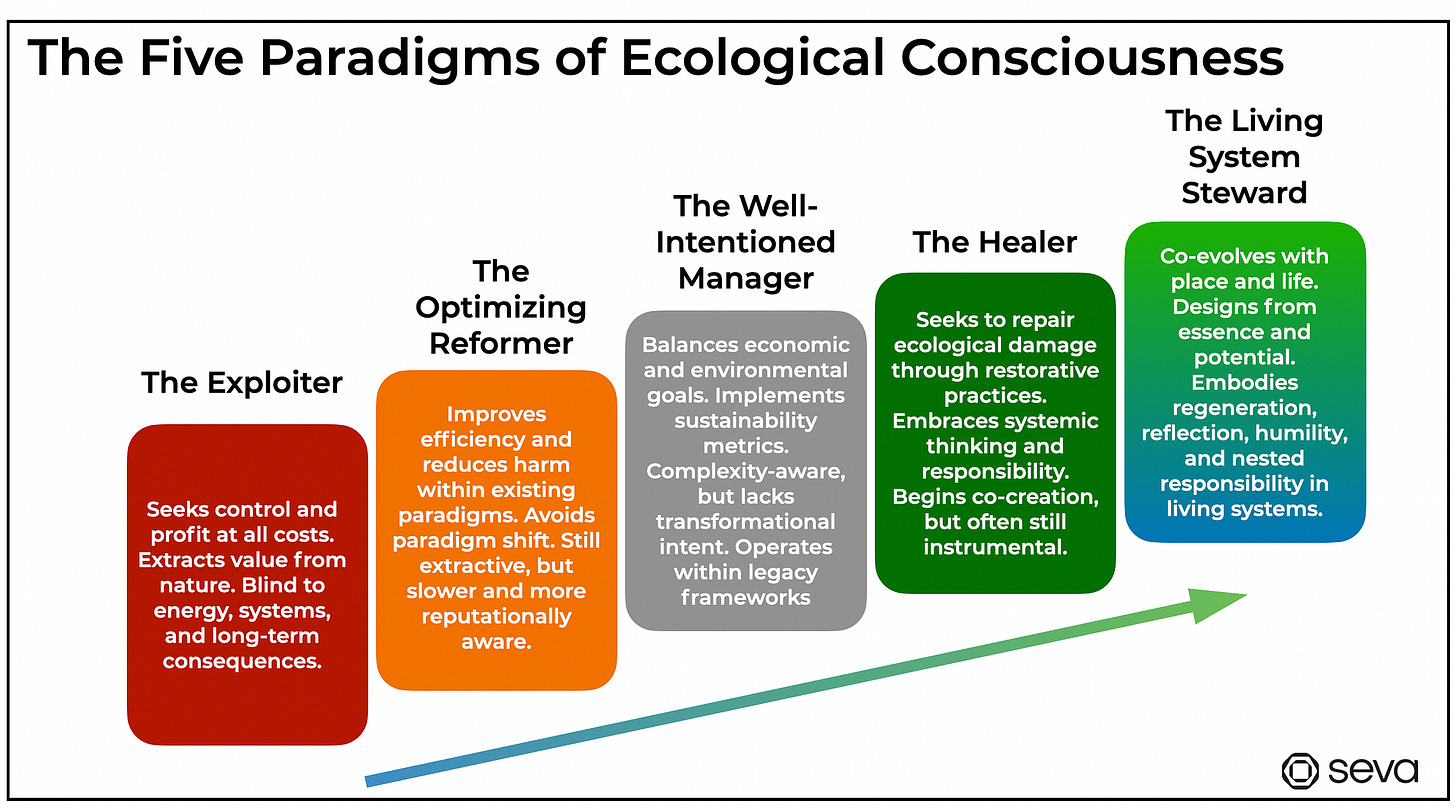

In this spirit, the following five archetypes are offered not as rigid categories, but as living patterns — recurring expressions of mindset and worldview observed across the ecosystem of ecological conversations, projects, and institutions.

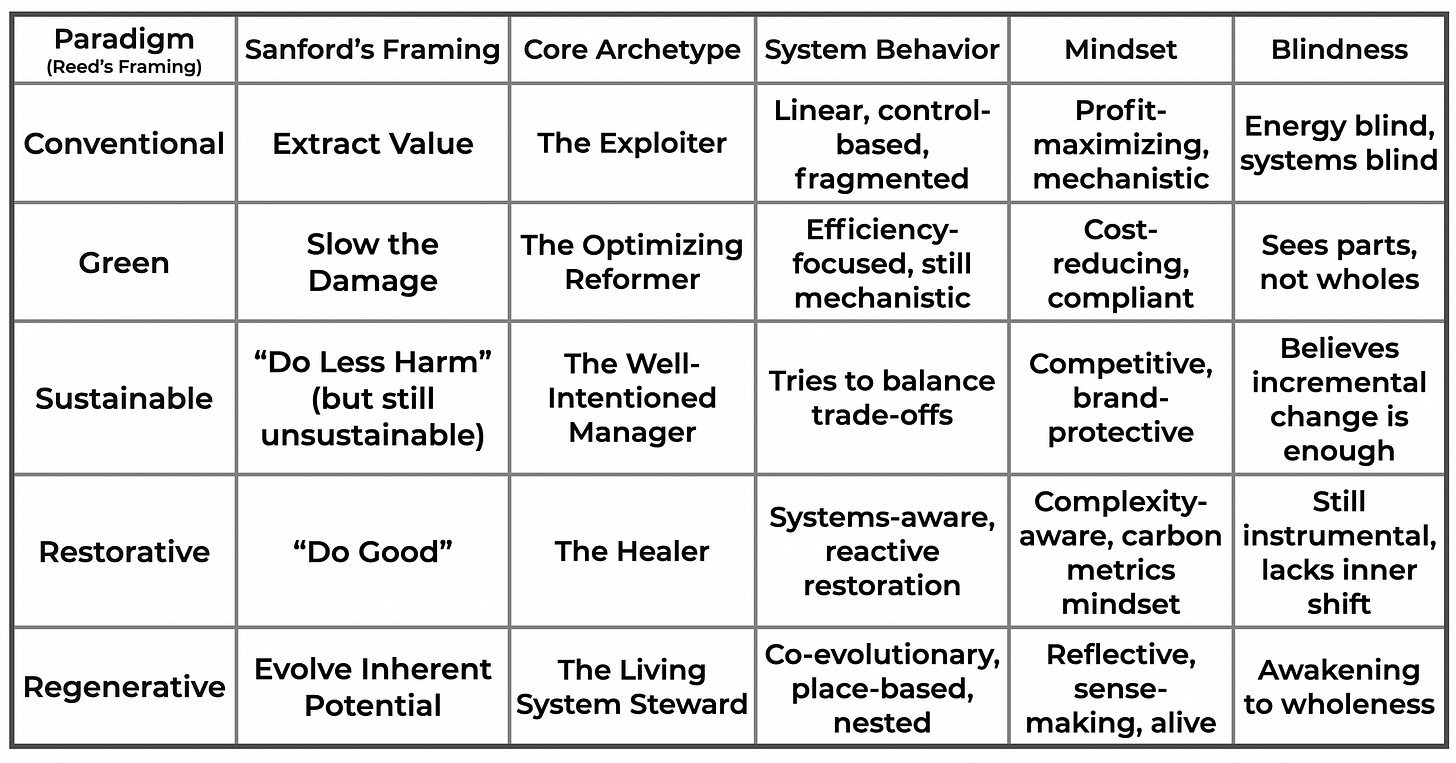

They emerged from a synthesis of Bill Reed’s five paradigms of ecological evolution and Carol Sanford’s developmental framing, then translated through the lens of lived experience: in fieldwork, boardrooms, fundraising meetings, land stewardship conversations, and policy design.

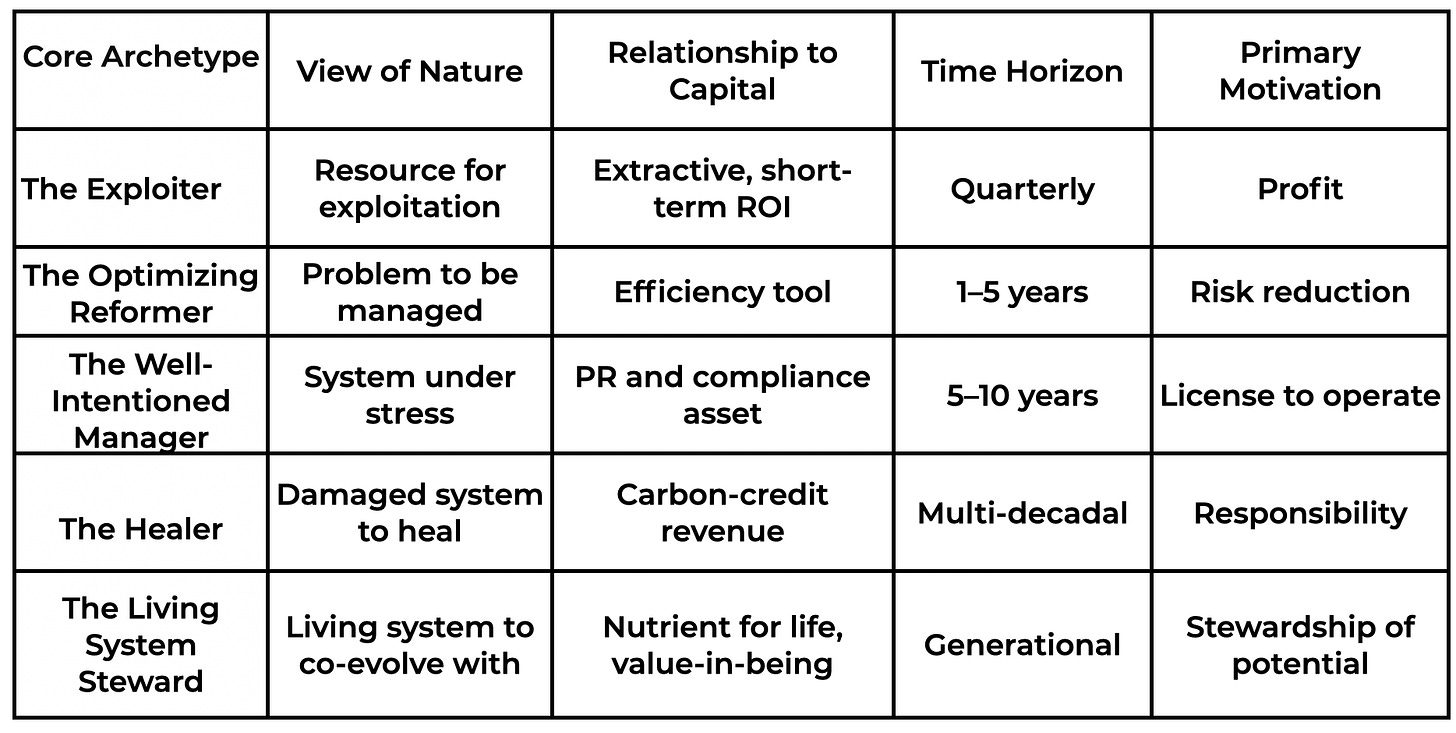

Each archetype holds a distinct relationship to nature, value, complexity, and time. Each one speaks a different language — whether of control, compliance, restoration, or co-evolution.

Recognizing these archetypes allows us to better understand where someone is coming from, not to dismiss them, but to meet them there — and gently stretch the conversation toward deeper coherence with life. As with all developmental models, this is a simplification. But it is a useful one — especially in a time when language about regeneration is spreading faster than the consciousness required to embody it.

Naming these archetypes helps us ask: What paradigm is operating here? What needs to shift for this project, this partner, this team, to truly align with a regenerative future?

This is not just a taxonomy of strategies. It is a map of the human soul in its relationship to life.

What if we could see each paradigm as an archetype — not just a phase of thought, but a profile of behavior, system orientation, and energetic consciousness? What if the real shift is not from bad to good, but from dead to alive?

Below, we trace this path — not just through ideas, but through the types of people, systems, and worldviews they carry.

The Five Paradigms of Ecological Consciousness

Behavioral Signatures of Each Paradigm

From Blindness to Seeing: The Evolution of Awareness

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.” — Carl Jung

Levels of consciuosness

Energy Blind (Hagens): Paradigm 1–3 lack any awareness of the energy foundations of life and economy.

Systems Blind: Paradigm 1–2 act within silos; 3 begins to sense interconnections.

Living System-Aware: Only in 4–5 do we begin to understand nestedness, essence, and vitality.

The threshold between restorative and regenerative is a spiritual one.

It is not about better data. It is about a different way of seeing.

From Extraction to Regeneration: The Five Ecological Archetypes

1. The Exploiter (Conventional Paradigm: Extract Value)

Behavioral Traits

Seeks short-term profit and control

Treats problems as isolated and external

Prefers linear plans, efficiency, and predictability

Avoids regulation, externalities ignored

Worldview / Value Logic

Nature is inert capital

Success = profit and scale

Optimization = control over variables

Relationship to Nature

Nature is a warehouse of resources

Only value is extraction (timber, minerals, crops)

Language & Mental Models

“Return on investment”

“We need to increase output”

“What’s the yield per hectare?”

Blind Spots

Energy and systems blindness

Ignores feedback loops and unintended consequences

Doesn’t see depletion until it’s too late

Evolutionary Edge

Needs to awaken to interdependence and limits

Must internalize the cost of externalities

2. The Optimizing Reformer (Green Paradigm: Slow the Damage)

Behavioral Traits

Seeks eco-efficiency without changing the core system

Implements recycling, certifications, and offsets

Driven by risk management, PR, or early compliance

Worldview / Value Logic

Nature is a variable to manage

Optimization = reduce harm without sacrificing profit

“Doing less bad” is the goal

Relationship to Nature

Nature is a fragile system that must be protected from humans

Still othering — “us” managing “it”

Language & Mental Models

“Offsetting our footprint”

“Green certifications”

“Eco-friendly packaging”

Blind Spots

Fragmented systems view

Belief in techno-fixes and incremental change

Doesn’t question root causes or paradigms

Evolutionary Edge

Needs to shift from harm reduction to co-evolution

Must move from compliance to relationship

3. The Well-Intentioned Manager (Sustainable Paradigm: Do Less Harm)

Behavioral Traits

Balances stakeholder needs

Embraces ESG metrics and circular economy

Thinks in triple-bottom-line terms

Invests in resilience but still within extractive logic

Worldview / Value Logic

Nature is a stakeholder

Trade-offs are inevitable

Stability is prized, even at the cost of potential

Relationship to Nature

Nature is a system under stress

“Stewardship” in a managerial sense

Language & Mental Models

“Sustainable development goals”

“Carbon neutral by 2050”

“Doing well by doing good”

Blind Spots

Hidden belief in separateness

Thinks system can be sustained without transformation

Still energy blind and instrumental

Evolutionary Edge

Must shift from balance to vitality

Needs to release control and embrace emergence

4. The Healer (Restorative Paradigm: Do Good)

Behavioral Traits

Understands damage has been done and seeks repair

Implements regenerative agriculture, rewilding, offsets

Begins to collaborate with local communities and ecology

Worldview / Value Logic

Nature is wounded and needs healing

Capital is a tool for repair

Feedback loops and systems are visible

Relationship to Nature

Nature is a living system, but still separate

We help “it” recover

Language & Mental Models

“Restoration project”

“Offsetting carbon impact”

“Giving back to the land”

Blind Spots

Healing can be transactional

May miss the deeper shift from separateness to wholeness

Still measuring by reduction, not potential

Evolutionary Edge

Must move from restoration to co-evolution

Needs to see life as a partner, not a patient

5. The Living System Steward (Regenerative Paradigm: Evolve Potential)

Behavioral Traits

Designs from wholeness and uniqueness of place

Sees humans and nature as co-evolving partners

Builds capacity, not dependency

Reflective, relational, long-term thinker

Worldview / Value Logic

Nature is alive and intelligent

Value = vitality, adaptability, coherence

Each system has an essence and role in the whole

Relationship to Nature

Nature is not separate — it’s self

Stewardship is co-participation in life’s unfolding

Language & Mental Models

“We are part of the forest’s story”

“Unfolding potential”

“Essence, nestedness, reciprocity”

Blind Spots

May be hard to scale in traditional sense

Requires inner development and cultural shift

Can sound esoteric to lower paradigms

Evolutionary Edge

Must remain humble, adaptive, and rooted

Keep aligning insight with action across systems

Beyond Frameworks: Toward a Regenerative Mind

It’s important to clarify that this is not an attempt to compare, benchmark, or overlay existing models of consciousness such as Spiral Dynamics or integral stage theories. What we’re exploring here is more grounded and practical — rooted in the lived dynamics of ecological work and system design.

People tend to operate from within a paradigm, and these paradigms — whether extractive, restorative, or regenerative — are not simply choices. They are states of perception, of relational awareness, of what one sees as possible or real.

Through years of writing and dialogue, I’ve come to recognize that the true shift we are seeking is not just behavioral or technological, but deeply ontological.

It is a shift in how we see ourselves in relation to life — a movement from separation to wholeness, from dominion to participation, from exploitation to inter-being and ultimately inter-becoming with the living world. This framework, then, is not about classification.

It is an invitation to notice the field — to observe the stories, assumptions, and language that reveal which paradigm is present in a room, in a project, or in ourselves.

Truly amazing and valuable post Ernesto!

– Wouldn’t it be great to have this in the format of an online interactive presentation — like in Canva — and connecting the dialogue with readers in a community forum — like in Hylo?

– Would you perhaps need support in setting that up effectively?

This is a powerful model - thank you Ernesto. I've printed it to hang above my desk. Right now I am reading so much on sustainability, governance and economics and sorting through the various streams of thought and campaigns can be confusing. This model offers a way of holding the many voices. It also reminds me that my spiritual path and connection the land are intrinsic to this work. Which should be obvious but easy to forget sometimes.